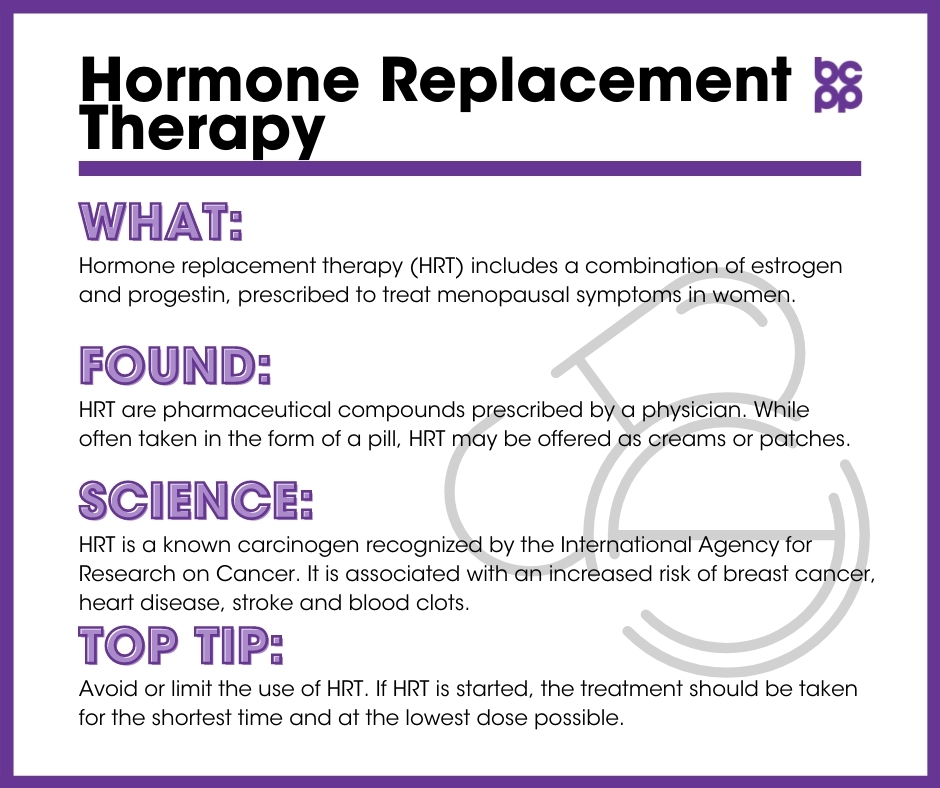

Hormone Replacement Therapy

At a Glance

Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) often includes a combination of estrogen and progestin, prescribed to treat menopausal symptoms in women. HRT that combines both estrogen and progesterone on a daily basis is a known carcinogen recognized by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) that has been associated with an increased risk of breast cancer, heart disease, stroke and blood clots. Studies show that estrogen only hormone therapy carries less breast cancer risk compared to combined (estrogen + progesterone) but is an option only for those women still menstruating. While estrogen-only carries lower breast cancer risk, it elevates endometrial (uterine) cancer risk.

Overview

Oral contraceptives, consisting of estrogen and progestogen, possess both cancer-causing and cancer preventive properties (see Table below). As oral contraceptives are used by healthy individuals any decision to use these drugs should be based on a thorough evaluation of the risk profile by your medical care provider. Use of oral contraceptives is associated with a small excess risk of cancers of the breast, cervix, and liver; however, the use of these drugs also protects against endometrial and ovarian cancer. Therefore, from a cancer perspective, no clear recommendation can be given.[25]

Studies show that estrogen only hormone therapy carries less breast cancer risk compared to combined (estrogen + progesterone) HRT, depending on type and length of treatment. Estrogen only vaginal cream carried the lowest risks with increasing breast cancer risk from patches, pills, and longer duration (5+ years) of use. However, estrogen only hormone therapy carries increased endometrial (uterine) risk. Additionally, estrogen only therapy can only be used among women who are still menstruating.

Though in the early stages, some experimental data in laboratory animals indicate beneficial cognitive effects of bio-identical estrogen (17β-estradiol) during the peri-menopausal period when estrogen receptor alpha is still present (during perimenopause and early menopause). More research is needed in this area to confirm findings but this line of research is advancing our ability to characterize the complex role of estrogen in women’s health.[23-24]

Table 1. Hormone drug types and cancer associations. Source: World Health Organization. International Agency for Research on Cancer. European Code Against Cancer.

What are traditional hormone replacement therapy (HRT) and Bioidentical compounds (BiCs)?

HRT is generally prescribed for menopausal symptoms. Most standard formulations include both estrogen and progestin components, with both the estrogen and the progestin being in a synthetic form. Conjugated equine estrogen and ethinylestradiol are commonly used estrogens; medroxyprogesterone acetate or norethisterone acetate are common progestins used in these formulations. Estrogen-only HRT can be prescribed, but only for women who have previously undergone surgical hysterectomies.

Because of concerns about potential health effects of using synthetic-hormone based HRT, many women have moved to taking ‘Bioidentical Compounds’ (BiCs), or compounds that contain estradiol (or another natural estrogen) and progesterone, chemicals that are normally produced by the ovary across the normal menstrual cycle, but are actually synthesized from plant estrogens for use in BiCs.

While the components of traditional HRT are described by pharmaceutical companies on packaging in the formulations, BiCs have varying formulations, sometimes being custom-mixed for an individual woman.

Where is hormone replacement therapy found?

Both HRT and BiCs are pharmaceutical compounds and must be prescribed by a physician. While commonly taken in the form of a pill, both forms of hormone treatment may also be offered as creams or patches.

What evidence links hormone replacement therapy to breast cancer?

A systematic review of 14 studies examined breast cancer risk with both estrogen-only or combined hormone replacement therapy. Researchers found estrogen-only therapy was not significantly associated with breast cancer in both randomized control trials and observational studies. However, in the analysis of combined estradiol-progestogen therapy, researchers found that those taking estrogen and progestogen (a type of synthetic progesterone) had 1.5 times higher risk (95% certainty of 1.03-2.2 times higher risk) compared with those who weren’t taking it. Those women taking estrogen and progestogen for more than five years had 2.4 times higher risk (95% certainty of 1.8-3.3 times higher risk) compared to those who took it for less than five years. While it was concluded that estradiol-only therapy carries no significant risk for breast cancer, the risk of breast cancer with combined therapy varied according to the type of progestogen and the duration. Estradiol therapy combined with medroxyprogesterone, norethisterone and levonorgestrel was associated with an increased risk of breast cancer, while estradiol therapy combined with dydrogesterone and progesterone carried no risk.[20]

Several studies have found an increased risk of breast cancer in people using combined HRT and increased risk of endometrial (uterine) cancer in women taking estrogen only pills.

- The Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) was a clinical trial and observational study designed to explore the benefits and risks of combined estrogen-progestin HRT in post-menopausal women. In 2002, the project was halted prior to the end of the study, because researchers observed a significant increase in the relative risk of breast cancer.[1],[2]

- Analyses of a second arm of the WHI study clarified that the increased risk of breast cancer detected in the study occurred in women taking the combined estrogen-progestin formula, while a decreased risk for breast cancer was found among women taking estrogen-only HRT supplements.[3],[4]

- A 2012 WHI follow-up study was conducted among women with a hysterectomy taking estrogen-only therapy (n = 7,645). Researchers found a reduced risk of breast cancer and reduced mortality from breast cancer among those taking estrogen only. Further analysis showed the reduced breast cancer risk was concentrated in women without benign breast disease or a family history of breast cancer.[7]

- A 1993 study found that menopausal women taking estrogen only significantly increased endometrial cancer risk (3 times higher risk with 95% certainty of 1.7-5.1 times higher). Although women who used low-dose preparations exclusively had the lowest risk. And those women using estrogen injections or creams, were not significant risk factors after adjustment for estrogen pill use.[22]

- Swedish researchers halted a five-year study in 2003 after only two years because women with a history of breast cancer taking the combined estrogen-progestin HRT had a significant increase in new tumors compared to women who received other treatments for menopausal symptoms.[5]

- In 2003, researchers in the Million Women Study (MWS) in the United Kingdom reported the then-current use of all types of post-menopausal HRT significantly increased the risk of breast cancer.[6],[7] Again, the risk was greatest among users of estrogen-progestin combination therapy.

- Through a California statewide registry and California Health Interview Survey of almost 3 million women, researchers confirmed that combined HRT increases the risk of breast cancer in post-menopausal women, and that stopping use of the combination pill leads to decreased risk of developing breast cancer. Decreased incidence in breast cancer was highest (22.6%) in groups with the greatest decline in using HRT, reducing to 13.9% in moderate HRT use, and smallest (8.8%) with least decline in HRT use.[8]

- A Danish study followed for about 18 years almost 30,000 women aged 50-64 at the beginning of the study. Researchers found that use of HRT use was associated with a significant increased risk in development of breast cancer. The only type of HRT not associated with breast cancer in this study was local use or vaginal estrogen application only (as opposed to oral and transdermal HRT). Alcohol consumption also increased breast cancer risk, and together, alcohol and HRT combined to create a greater risk.[9]

What evidence links bioidentical compounds to breast cancer?

Studies on bioidentical compounds are more difficult to conduct because the formulations are often personalized, so the dosage may not be standardized. Their use is more recent so there has been less time for extensive follow-up. Nevertheless, there have been a few important studies in the area.

- In a systematic review of published articles on the use of progesterone as part of hormone therapy formulations, the authors concluded that there was no indication of increased risk of breast cancer for women who had taken combined estradiol-progesterone treatments for less than five years. They found ‘limited evidence’ that there was a slightly increased risk for developing breast cancer when the BiCs were taken for more than five years.[10]

- A study found that women taking bioidentical progesterone had a lower risk of developing invasive breast cancer than women taking a synthetic progesterone.[11]

- Researchers found that women who had undergone surgical removal of the uterus and who initiated use of BiC estrogen (estradiol) alone had a decreased risk of developing breast cancer. However, the synthetic estrogens used in traditional HRT decrease breast cancer risk at a greater magnitude than the natural or bioidentical form. Similarly, when paired with synthetic progestins, the bioidentical form of estrogen is less effective than the synthetic forms found in HRT.[12]

What about effects of taking HRT or BiCs by women who have been diagnosed with breast cancer?

- Swedish researchers examined the effects of taking HRT for 2 years following treatment for metastatic breast cancer. As compared to breast cancer survivors who did not take HRT, those taking the compound had an increased risk of a new breast cancer event—either a recurrence of the previously diagnosed cancer or diagnosis of a new, contralateral cancer. At the end of the 5-year follow-up, there was no difference in either the risk of distant metastasis of breast cancer, nor of mortality.[13]

- A qualitative summary of the safety of HRT use following diagnosis with breast cancer reported that many of the studies were poorly designed and sometimes contradictory. The researchers concluded that, “There are currently no reassuring data indicating the absence of a harmful effect of” HRT in women who have been treated for breast cancer.[14]

Who is most likely to be exposed to hormone replacement therapy?

Women who are experiencing menopausal symptoms and have been prescribed HRT by their physician.[15]

Who is most vulnerable to health effects of hormone replacement therapy?

A study examining the possible interactions between use of HRT and race, weight and breast density found that HRT use increased risk for breast cancer in White, Asian and Hispanic women, but not Black women. It is important to note there was no interaction between HRT use and either body mass index or breast density.[16]

Similar data for different ethnicities have not been conducted for BiCs. The American College of Clinical Endocrinologists and the American College of Endocrinologists,[17] along with the U.S. Preventive Task Force,[18] all recommend against the use of BiCs because of potential adverse health effects, including increased risk of developing breast cancer.

What are the top tips to avoid exposure?

Limit use. The IARC advises that, if possible, you should avoid or limit the use of hormone replacement therapy. If HRT is started, the treatment should be taken for the shortest time and at the lowest dose possible to control the symptoms of menopause. Lowest risks are associated with vaginal gels and higher risks are report with patches and pills. The precise therapy should be discussed with the physician before starting treatment.[19]

Emerging Evidence

In a review of Estrogens, estrogen receptors, and female cognitive aging, authors summarized experimental data indicating beneficial effects of bio-identical estrogen (17β-estradiol) on cognition. Cholinergic function and hippocampal plasticity improved with estradiol exposure, both of which have been linked to the ability of estradiol to exert beneficial effects on cognition as long as estrogen receptor alpha is still present (during perimenopause and early menopause). These are early experimental findings in laboratory animals and have not yet been confirmed in the clinical setting. Nonetheless, these findings help characterize the complex role of estrogen in women’s health.[23-24]

Updated 2025

[1] Rossouw, Jacques E et al. “Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results From the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial.” JAMA 288, 3 (2002): 321-33. doi:10.1001/jama.288.3.321.

[2] Rossouw, Jacques E et al. “Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results From the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial.” JAMA 288, 3 (2002): 321-33. doi:10.1001/jama.288.3.321.

[3] Anderson, Garnet L et al. “Effects of conjugated equine estrogen in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial.” JAMA 291, 14 (2004): 1701-12. doi:10.1001/jama.291.14.1701.

[4] Anderson GL et al. “Conjugated equine oestrogen and breast cancer incidence and mortality in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: extended follow-up of the Women’s Health Initiative randomised placebo-controlled trial.” The Lancet Oncology 13, 5 (2012): 476-486. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(12)70075-x.

[5] Holmberg, L et al. “HABITS (hormonal replacement therapy after breast cancer–is it safe?), a randomised comparison: trial stopped.” Lancet 363, 9407 (2004): 453-5. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15493-7.

[6] Beral, Valerie, and Million Women Study Collaborators. “Breast cancer and hormone-replacement therapy in the Million Women Study.” Lancet 362, 9382 (2003): 419-27. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(03)14065-2.

[7] Anderson GL et al. “Conjugated equine oestrogen and breast cancer incidence and mortality in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: extended follow-up of the Women’s Health Initiative randomised placebo-controlled trial.” The Lancet Oncology 13, 5 (2012): 476-486. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(12)70075-x.

[8] Robbins, Anthony S, and Christina A Clarke. “Regional changes in hormone therapy use and breast cancer incidence in California from 2001 to 2004.” Journal of Clinical Oncology 25, 23 (2007): 3437-9. doi:10.1200/JCO.2007.11.4132.

[9] Holm, Marianne et al. “The Influence of Menopausal Hormone Therapy and Potential Lifestyle Interactions in Female Cancer Development-a Population-Based Prospective Study.” Hormones & Cancer 9, 4 (2018): 254-264. doi:10.1007/s12672-018-0338-5.

[10] Stute P, L. Wildt and J. Neulen. “The impact of micronized progesterone on breast cancer risk: a systematic review.” Climacteric 21, 2 (2018): 111-122. doi:10.1080/13697137.2017.1421925.

[11] Davis, Ruth, Pelin Batur and Holly L Thacker. “Risks and effectiveness of compounded bioidentical hormone therapy: a case series.” Journal of Women’s Health (2002) 23, 8 (2014): 642-8. doi:10.1089/jwh.2014.4770.

[12] Zeng, Zexian et al. “Conjugated equine estrogen and medroxyprogesterone acetate are associated with decreased risk of breast cancer relative to bioidentical hormone therapy and controls.” PloS One 13, 5 (2018): e0197064. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0197064.

[13] Holmberg, Lars et al. “Increased risk of recurrence after hormone replacement therapy in breast cancer survivors.” Journal of the National Cancer Institute 100, 7 (2008): 475-82. doi:10.1093/jnci/djn058.

[14] Antoine C et al. “Safety of hormone therapy after breast cancer: a qualitative systematic review.” Human Reproduction 22, 2 (2007): 616–622. doi:10.1093/humrep/del393.

[15] Files, Julia, Marcia G Ko and Sandhya Pruthi. “Bioidentical hormone therapy.” Mayo Clinic Proceedings 86, 7 (2011): 673-80. doi:10.4065/mcp.2010.0714.

[16] Hou, Ningqi et al. “Hormone replacement therapy and breast cancer: heterogeneous risks by race, weight, and breast density.” Journal of the National Cancer Institute 105, 18 (2013): 1365-72. doi:10.1093/jnci/djt207.

[17] Cobin, Rhoda H et al. “American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology Position Sstatement on Menopause-2017 Update.” Endocrine Practice 23, 7 (2017): 869-880. doi:10.4158/EP171828.PS.

[18] Gartlehner, Gerald et al. “Hormone Therapy for the Primary Prevention of Chronic Conditions in Postmenopausal Women: Evidence Report and Systematic Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force.” JAMA 318, 22 (2017): 2234-2249. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.16952.

[19] International Agency for Research on Cancer. “European Code Against Cancer: 12 Ways to Reduce Your Cancer Risk.” Last modified 2016. http://cancer-code-europe.iarc.fr/index.php/en/ecac-12-ways/pharmaceutical-drugs/questions/68-hormone-replacement-therapy.

[20] Yang, Z., Hu, Y., Zhang, J., Xu, L., Zeng, R., & Kang, D. (2016). Estradiol therapy and breast cancer risk in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gynecological Endocrinology, 33(2), 87–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/09513590.2016.1248932

[21] Furness S, Roberts H, Marjoribanks J, Lethaby A. Hormone therapy in postmenopausal women and risk of endometrial hyperplasia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Aug 15;2012(8):CD000402. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000402.pub4. PMID: 22895916; PMCID: PMC7039145. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7039145/

[22] Brinton, LA, Hoover, RN. Estrogen Replacement Therapy and Endometrial Cancer Risk: Unresolved Issues. Obstetrics & Gynecology 81(2):p 265-271, February 1993. PMID: 8380913. Link to study.

[23] Jill M. Daniel, Estrogens, estrogen receptors, and female cognitive aging: The impact of timing, Hormones and Behavior, Volume 63, Issue 2, 2013, Pages 231-237, ISSN 0018-506X, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yhbeh.2012.05.003.

[24] Barbara B. Sherwin. Estrogen and memory in women: how can we reconcile the findings?. Hormones and Behavior,

Volume 47(3) 2005, Pages 371-375, ISSN 0018-506X, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yhbeh.2004.12.002.

[25] World Health Organization. International Agency for Research on Cancer. European Code Against cancer. https://cancer-code-europe.iarc.fr/index.php/en/ecac-12-ways/pharmaceutical-drugs/questions/36-category-all/categories-en/12-ways/pharmaceutical-drugs/box/101-box-1-hormonal-treatments

Types: Article